(Lois) Weaver: What is a Study Room Guide?

(Lois) Keidan: LADA’s Study Room is a free, open access collection of Live Art related books, journals, DVDs, VHS tapes, objects, and digital files. The space is used by artists, students, scholars, writers, and curators, and by groups of artists, students and others.

We never intended to have a Study Room, but when we first set up the Agency in 1999 we had a collection of performance documentation and publications that we’d brought with us from our work at the ICA and people began phoning to ask if they could come and view these materials. We realized that we were holding some fairly rare and special documentation and that we should build on this and create a resource where all kinds of people could access a growing body of Live Art documentation and publications. And since 1999 the Study Room has grown into one of the world’s largest Live Art libraries.

Once we’d set up the Study Room we soon found that many visitors wanted recommendations of titles to look at, particularly around themes they were researching or issues that were of interest to them. Whilst we found the process of recommending titles hugely enjoyable, we were also aware that we were often directing people to the same titles and that other people might recommend different materials. For example, in the early 2000s most enquiries we received were around the body in performance and we sensed that we were always recommending the same artists – Franko B, Ron Athey, Kira O’Reilly etc – and that actually Franko himself might suggest different artists to explore. And so we commissioned Franko to create a personal Guide to some of the materials we held on the body in performance. Franko’s Guide (in the form of an interview with Dominic Johnson) was a huge hit and we haven’t looked back since.

Study Room, 2013

We now have over 20 Guides and try to commission around two or three new Guides each year.

We commission Guides in response to a perceived interest in a particular theme, such as the body in performance, or around more ‘zeitgeist’ issues like the ethics of arts funding. The idea of the Guides is twofold – to help navigate users through the Study Room resource, experience the materials in a new way, and highlight materials that they may not have otherwise come across, but also to recommend key titles that we should acquire.

Commissioned artists are invited to approach the research and creation of their Guides in any way they want. The Guides themselves can take a number of forms – an extended essay, a series of chapters, an online blog, a list with footnotes – the only consideration is that they should be accessible in both form and content to a wide number of users.

Weaver: And why a Study Room Guide on Feminism and Live Art?

Keidan: In 2006 we started Restock, Rethink, Reflect, an ongoing series of initiatives for, and about, artists who are engaging with issues of identity politics and cultural diversity in innovative and radical ways, and which aims to map and mark the impact of art to these debates, whilst supporting future generations of artists through specialized professional development, resources, events and publications.

As Live Art is an interdisciplinary and ephemeral area of practice, there are many challenges to its documentation, archiving and contextualization, which can lead to the exclusion of significant artists and approaches from wider cultural discourses and art histories. This is particularly the case for culturally diverse artists, whose experiences and practices are often sidelined within UK’s cultural histories.

Restock, Rethink, Reflect sets out to address these challenges by marking the critical historical contributions of artists, mapping dynamic current practices and looking to the future. The first RRR was on Live Art and Race (2006-2008), the second was on Disability (2009-2012), and the third, and current, RRR is on Feminism and aims to map and mark the impact of performance on feminist histories and the contribution of artists to discourses around contemporary gender politics.

To do this we have the pleasure of working with you and Ellie Roberts on a research, dialogue and mapping project to develop the materials we hold on Feminist practices in the Study Room, particular lost, forgotten or invisible artists and moments and to create a new Study Room Guide offering all kinds of navigation routes through these materials. The Guide will exist in a physical form in the Study Room, and will also be developed as an online resource on our new website.

Keidan: Getting personal – when did you first become aware of feminist performance? What was it doing at the time? Who were the artists that first inspired you?

Weaver: I think I was doing it before I was fully aware of it. After becoming politicized in my final years at university by civil rights and anti war protests and having my mind opened by the radical potentials of experimental theater of the sixties and early 1970s such as the Open Theatre, Manhattan Project and the Performance Group, I knew I wanted to MAKE theatre rather than BE IN the theatre. So when I graduated in 1972, I went fishing for ways to combine my new found politics with my love of theatre. Luckily two years later, I landed an opportunity to work with a group of women, gathered by Muriel Miguel. Muriel had been a member of the Open Theatre and was looking to move out of the shadows of the male practitioners who dominated the experimental theatre scene. We met once a week and talked about things, all kinds of things. We talked about the need for women to tell their own stories; we talked about taking ownership over ideas and approaches to theatre, we talked about mundane preoccupations, aggravating partners and dysfunctional families. Looking back, it was our own version of a consciousness raising group.

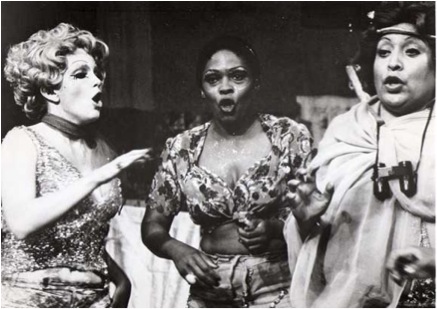

Spiderwoman Theater, image courtesy of Lois Weaver

Then after almost a year of weekly meetings, we were asked to do a performance for ‘New Music ‘ evening. It was then that we became Spiderwoman and began working with a concept that the director, Muriel Miguel, called storyweaving. From that we formed a company and began to use experimental theatre techniques, Native American storytelling traditions and popular humor to make work. Our first piece was a comedy called Women in Violence (1975). We did not start out as a feminist company. We were women who wanted to make work about our own experiences. Although we eventually identified AS a feminist company because of the make up of the group, our content and our cultural contexts, I’m sure we would not have been able to come up with one working definition of feminism amongst the 6 of us at that time or, in fact, throughout our 7 year history together. The experience of working with Muriel Miquel had the greatest influence on me both as a feminist and as a practitioner. As a feminist, Muriel had a very practical no nonsense approach to feminism and as a practitioner, she taught me to both respect and exploit the details of everyday and to use fantasy to empower both my work and my life.

From that working perspective I became aware of other feminist theatre companies, most of whom were using theatre based approaches. It’s Alright To Be a Woman Theatre (1971) was one of the first groups I heard about. They were working out of consciousness raising groups and using agitprop strategies to move those political initiatives into a more public forum. They were looking to create a collective form of theatre whose structure resisted the conventional separation of roles such as director, actor, audience and whose material validated women’s personal lives. However the groups I became most familiar with, and who influenced me at that point, were initiated by other women who had worked in the Open Theatre and were looking to find their own voices and set up their own companies. Roberta Sklar and Sondra Segal of Women’s Experimental Theatre (1975) were working out of Women’s Interart Theatre (opened in 1971), a space committed to the development and presentation of women artists in the performing, visual and media art. Roberta set up WET up as a formal company and through the use of audience participation and personal narrative rewrote and re-imagined canonical texts, most notably Greek plays and myths, in order to ask contemporary questions about sexuality and gender. Although, I had already moved away from this form of theatre, I was still impressed by Roberta and her fierce embodiment of the auteur director.

Another powerful role model for me was Megan Terry, a playwright who had been a founding member of the Open Theatre. Megan developed many of Open theatre’s early aesthetic experiments and was instrumental in applying those aesthetic processes to current political issues like the war in Vietnam. However, like Roberta Sklar and Muriel Miquel, Megan left the Open Theatre whose collective work had become identified primarily with the work of one man, Joe Chaikin. She founded the Omaha Magic Theatre in Nebraska (1968) with her partner Jo Ann Schmidman. I was clearly drawn to this Open Theatre way of making theatre that used a collaborative process to explore political, artistic, and social issues and viewed the performance as a continuing process rather than an end product. I recognized from these women the need to maintain an individual voice in a collaborative process but also understood the importance of building creative company and fostering community.

Although I was mainly working within an experimental theatre context, my eye did wander from time to time. I was mystified and delighted by witnessing incarnations of The Education of a Girl Child (1972-1973) by Meredith Monk. I used to peek into a storefront theatre space literally next door to one of the Spiderwoman’s early venues. The theatre was called Time and Space Ltd (1973) and housed the vision of Linda Mussman. Once inside this space, which was a theatre yet not a theater, words and objects were interchangeable and time refused to provide any connection to what was seen and heard. I was fascinated with this focus on aesthetic experiment that still somehow maintained a personal and political undertone. Although it felt somewhat foreign, this work opened my eyes to possibilities beyond feminist narrative and storytelling.

Heresies A Feminist Publication on Art & Politics. Vol. 4, No. 2 (Issue 14)

Excited by the creation of my own theatre practice but blinkered by my immersion in it, I was not as aware or involved with feminist visual artists until much later. I was more aware of the beginnings of institutions and contexts that supported women who were working with these approaches. Among these were the A.I.R Gallery (1972) a coop that supported exhibitions by feminist artists; Martha Wilson’s Franklin Furnace (1976), set up to advocate for politically and aesthetically marginal art forms and the New York Feminist Art Institute (1979) which in some ways operated primarily as a school and offered training and support in a feminist context. Looking back I can see these influences in my keen awareness of the need for sympathetic infrastructures and my desire to include the building of this kind of community support in my practice. I suppose the period at the end of this long sentence describing how I came be aware of feminist performance was when I met Sue Heinneman. Sue was a neighbor and a member of the Heresies Collective, a group of feminist artists who began working together in the early 1970s and produced Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics until 1992. The artists represented and the theory interrogated by this publication took me down some new roads that led from the intersection of art and feminism.

Weaver: Now I am returning the question. At what point did feminism begin to infiltrate your practice as a curator and arts advocate? Was there a particular piece of work or moment, and what have been some of the key points in your own career where art and feminism have crossed paths?

Keidan: The immediate answer is “I don’t really know”, partly because I’ve never thought about my having a ‘practice’ as such or about it in this way, and partly because I’ve got an unreliable memory, but here goes…

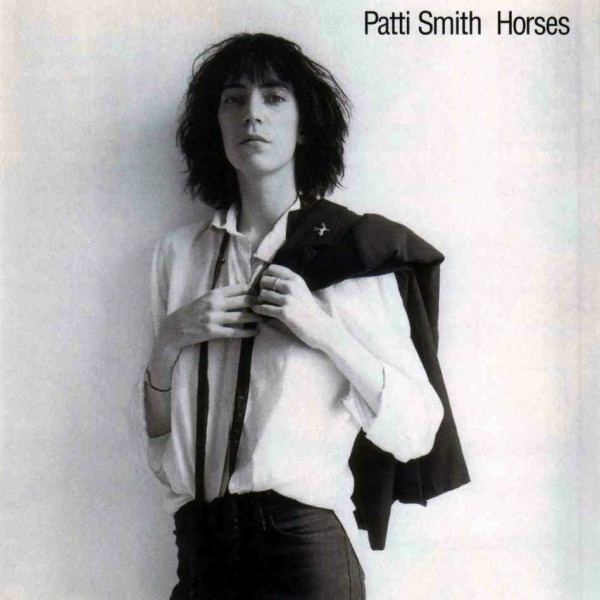

The first time I saw and heard Patti Smith’s Horses in the late 1970s was a huge moment for a young me, and seeing Laurie Anderson perform in Edinburgh in the early 1980s was seismic. In both instances these were inspirational, ground breaking and ‘formidable’ women artists working with music, but I didn’t at the time think of them as ‘feminist’ (I, naively, didn’t associate them with zealous ‘bra-burning’ (although Smith famously doesn’t wear a bra)). I also didn’t think about the visual artists I loved, like Diane Arbus and Cindy Sherman, in terms of feminist politics. Similarly punk and post-punk stars like Polystyrene, The Slits, Debbie Harry, Chrissie Hind etc were of huge cultural significance, but I didn’t necessarily think of them as ‘artists’ (I do now – now I know what art really is). The theatre makers and performance artists who I was most aware of in the formative early/mid 1980s were figures like Joseph Beuys and Tadeus Kantor and the many experimental companies who came to Edinburgh for the Festival (and Fringe) each year, like Lumiere & Son. I have to confess that most self declared feminist ‘performers’ I was aware of were, without naming names, making painfully dreary shows which were, for me at least, counter productive to a feminist cause! And then along came Blood Group.

Patti Smith, ‘Horses’ album cover

Blood Group was Anna Furse’s London-based performance company. She came to Theatre Workshop in Edinburgh where I was working in 1984-ish to create a participatory performance project with various groups associated with the Workshop. The project they developed was based on Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (this was before the Sally Potter/Tilda Swinton movie of 1992) and it involved all the things I’d grown to love about ‘performance art’ and ‘experimental theatre’. Most importantly, whichever way you looked at the project – and it was a brilliant project – it was feminist performance.

Anna not only introduced me, and many others, to performance thinking, making and producing from a feminist perspective, but also introduced me to the pioneering producer Judith Knight at Artsadmin (Anna also introduced me to The Wooster Group, for which I am also eternally grateful). In 1985 I met curator Nikki Milican when she brought Rose English and Anne Seagrave to the Fringe and then took me away to work with her at The Midland Group, Nottingham. While I was at the Midland Group I encountered other women who became huge influences on me, like Claire MacDonald and Geraldine Pilgrim, and saw the work of artists like Annie Griffin and Mona Hatoum. And then I moved to London to work with Michael Morris at the ICA and the possibilities of feminist performance really opened up for me. Since then I’ve had the pleasure of finding out about some of the most brilliant feminist artists, curators and thinkers in the world, and the privilege of working with some of them.

So I guess ‘the moment’ was Edinburgh, or to be precise, my time in Edinburgh, as it was mainly the artists and producers visiting from England that were my ‘gateway’. I mention this in relation to the key points where art and feminism have crossed paths in my voyage through feminist performance, because the cultural scene in Scotland was particularly macho, and the most feted movers and shakers were pretty much all men (Demarco, McGrath, Boyle, Wylie et al). This didn’t seem ‘normal’ to me as I’d grown up in a matriarchal family in Liverpool, a city dominated by strong women, had been to a school run by smart, independent women, and was regularly taken to the Everyman Theatre which was as egalitarian (and experimental) as it seemed possible to get. But I soon realised it was the norm. I was aware that representations of women, and the role of women, in mainstream culture and politics were repressive and oppressive, but when I started working (first in the music scene before I went to Theatre Workshop, The Midland Group and the ICA) I was genuinely shocked that even within the supposedly liberal world of ‘culture’, institutionalised sexism and implicit misogyny was endemic. Things are better today, but only just, and not enough. What was so significant about Judith, Nikki and other women like Rose Fenton and Lucy Neal of LIFT and Val Bourne of Dance Umbrella, was that, fed up with the way things worked, they had set up their own organisations to enable them to operate in new, autonomous ways to support new forms of performance. The achievements of these amazing women are, for me, key points where art and feminism have crossed paths. The only times in my working life when I haven’t been accountable, and felt inferior to, privileged white men was when I ran my own record label in the 1980s and co-founded LADA in the 1990s.

‘The Turning World: Stories from the London International Festival of Theatre’ by Rose Fenton and Lucy Neal

Other key points where art and feminism have crossed in my ‘career’ would include collaborations with you; attempting to create a more level playing field for socially and culturally marginalized artists through Arts Council policy, ICA programmes, and LADA initiatives; and the opportunity to experience the art and ideas of some of the most incredible women artists who have shaped how I think about the world (see my map).

I should add that, although I was far too young to be aware of it at the time (just as I wasn’t aware that Patti Smith could be a feminist icon or that Cindy Sherman’s work could be seen within feminist discourses or even be considered performative), another key influence on me and a moment where art and feminism crossed paths, was the 1970 Miss World competition. Back then kids, Miss World was a mainstay of primetime television – an annual celebration of misogyny that set the cause of women back decades, even centuries. The 1970 competition was hosted by Bob Hope in London and there was a stage invasion by the newly formed Women’s Liberation Movement who shouted ‘feminist’ slogans and chucked smoke and flour bombs onstage – live on TV!! That, and seeing Tommy Smith’s Black Panther salute at the 1968 Olympic Games, were my first experiences of political activism and were, in hindsight, inspirational moments – they taught me that politics could be embodied, acted out and performed, and that disobedience, disruption and humour are powerful weapons in the struggle for equality.

Keidan: We’ve talked about our histories and influences, so let’s move on to where we’re at now – who are the contemporary artists and thinkers we should be pointing to in this Guide and in what ways (if any) are their practices and politics different from those who have gone before?

Weaver: Our collaborations are most definitely key points for me too. I think that those early events at the ICA, like Queer Bodies that brought Holly Hughes to the UK for the first time, and Club Girrls, which transplanted club artists like Marissa from the clubs into the ICA performance space, were quiet beginnings for this Restock, Rethink, Reflect project on Live Art and Feminism. However thinking back on these events, I realise I have missed quite a few steps between my early influences of the seventies and today’s Feminist Art. So I am going to catch up.

My bridge from early Spiderwoman to the world of fun feminist art was a few political drag queens who were themselves struggling with issues of female representation. Jimmy Camicia of Hot Peaches, who began his feminist education reading Doris Lessing and Dorothy Parker, and Bette Bourne from Bloolips, who refused traditional drag in favor of creative costumes for men who like frocks, both gave me an antidote to the restrictive rules of representation circulating in the feminist network of the 1970s and 1980s. It’s also how I met Peggy Shaw. Peggy Shaw, herself a king of drag before drag kings come on the scene, had toured with Hot Peaches and in 1978 ended up working with Spiderwoman. Together we eventually formed Split Britches. We toured to the UK with Split Britches in the 80s and ran into what seemed like a cavalry of women’s theatre groups. The group that had the greatest impact on me was the Cunning Stunts. It was the first time I had seem women recklessly combine feminist politics with wild surrealist imagery. I will never forget standing in a tent in Penzance in 1979 and watching these amazing women manage to get each audience member to attach a cabbage leaf to a continuous piece string in order to express some kind of group solidarity with the protagonist who happened to be a human-sized spider in a cage.

Split Britches, ‘Upwardly Mobile Home’, 1984, image courtesy of Lois Weaver

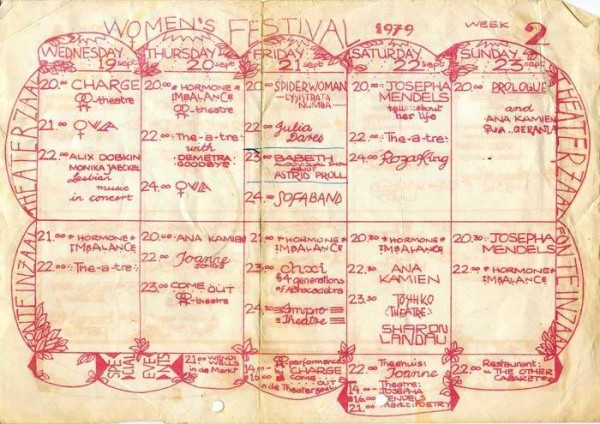

Our base at the time was 1980s Downtown New York where Peggy and I joined forces with a group of women in order to create a NY Women’s Festival in the style of those we had seen while touring in Europe in the late 70s. We ran 2 international festivals in 1980 and ’81 called WOW. We first used the term performance as opposed to theatre in the 1981 festival when we hosted a series of short pieces entitled Pasta and Performance. This was an odd dinner theatre where we enticed audiences to attend experimental performance work by providing them with a plate of spaghetti. I was intrigued by these, mostly dance-based performance artists such Yvonne Meir, the first person I had ever seen actually urinate on stage and Diane Torr, the first artist to put her go-go dancing and dancer friends on a theatre stage. Alexis Deveaux and the Flamboyant Ladies presented a performance of black lesbian desire in a production called No! that was so hot it literally started a fire in the venue and Blondell Cummings whose work I had seen in Meredith Monk’s company opened my eyes to the use of domestic in performance with her piece Chicken Soup, a portrait of lifetime domesticity. The WOW festivals in 1980 and 1981 also introduced me, and NYC, to international feminist companies and individuals artists such as Beryl and the Perils from the UK whose lyric ‘nothing could be finer than to be in your vagina in the morrrrning’ has most definitely influenced my use of song. Teatro Viola, from Italy, presented Shoeshow a performance with no formal ending, forever absolving me of having to take that particular responsibility for the audience.

1979 Women’s Festival in Amsterdam, image courtesy of Lois Weaver

I was aware of the work of artists like Carolee Schneemann, Rachel Rosenthal and Yvonne Rainer and fascinated by it but from a slightly uneducated distance. In those early WOW days we were intently focused on our downtown playground. WOW had started as a yearly festival but in 1983 became an ongoing performance space for women. It was a playful community and we played hard at establishing our lost and found aesthetic. We claimed and reclaimed butch/femme roles, camp for girls, lip-synch, vaudeville satire and shtick and we preformed multiple identities as outlaw feminists and explicitly sexual lesbians. Although we worked hard to get an audience it felt like we were doing it for ourselves. I think we were shocked when we looked up and found that other people were paying attention. However it provided a laboratory and a platform for artists like Holly Hughes and Carmelita Tropicana who continue to inspire me with their politics and humor.

While WOW was a source of fun and politics, PS122 became a source of aesthetic inspiration and to some extent aspiration. Pat Olesko’s massive inflatables were satisfying visual counterparts to what some of us had been struggling to put into words. Then of course there was the gloriousness of Annie Sprinkles and my favorite mistresses of meaningful chaos, Lucy Sexton and Annie Iobst of DanceNoise.

Weaver: So I have just about made it to the 90s and am about to shift my location and focus to the UK. Before we move on to now, I am wondering if you have thought of some of your other stops along the way.

Keidan: Well many of the artists who were huge influences on me in the 1980s and 90s are still active and still inspirational today – you, Patti Smith, Laurie Anderson, Karen Finley, Rose English, Anne Bean, Bobby Baker, Geraldine Pilgrim, Sonia Boyce, La Ribot, Stacy Makishi, The Guerilla Girls, Helen Paris & Leslie Hill, Marina Abramovic, Penny Arcade, Nao Bustamante, Coco Fusco et al. But I’ll take up your invitation to touch on a couple of other stops (artists and moments) along the way to NOW.

I missed most of the cavalry of women’s theatre groups in the UK that you encountered in the 80s. Groups like Beryl & The Perils and Cunning Stunts didn’t come to Scotland – or if they did I missed them. I did see, by accident rather than intent, an experimental theatre piece with a text by (I think) Bryony Lavery – I remember it had a profound impact on what I thought about theatre and what women could do on stage, but I can’t remember the name of the company or the show. Other than that the only feminist theatre company I remember visiting Edinburgh were Theatre Workshop Fringe regulars The Women’s Theatre Group, who were very serious indeed (apart from the time someone announced that Elizabeth Taylor was in the fancy knitwear shop round the corner and they turned into screaming teenagers). Edinburgh’s homegrown feminist theatre was, as I said earlier, pretty dreary stuff.

When I first arrived in London at the end of the 80s to work at the ICA, and then the Arts Council, I encountered artists who were making radical performance work from all kinds of directions. Artists like Monica Ross, Rose Garrard, Tina Keane, SuAndi, Annie Sprinkle, Karen Finley, Liz Aggiss, and others whose fierce and fearless work in socially engaged practices, dance, performance art, spoken word, and installation expanded, for me, both the possibilities of art/Live Art, and the possibilities of what an active feminist practice could be.

I returned to the ICA in the early 1990s, where, as well as the collaborations with you, Catherine Ugwu (LADA co founder) and I worked with Marina Abramovic, Maria Teresa Hincapie, Maris Bustamante, Jyll Bradley, Elia Arce, Orlan, Leslie Hill, Helen Paris, Rosa Sanchez, Susan Lewis, Stacy Makishi, Robbie McCauley, La Ribot and many, many more awesome women. Seeing these incredible artists perform to hungry, excited and, yes, packed audiences, many of who were a younger generation of women artists who grew up to be pretty amazing themselves, was genuinely exhilarating, and, I hope, in some way instrumental.

There are three significant things/moments I’d like to single out in relation to performance and feminism between the late 1990s/early 2000s and NOW –

- The Internet and other advances in technology have made the world a smaller place, bringing all kinds of artists out from margins. Technology has opened up new forms of border crossings and collaborations, offered new strategies and platforms for ‘empowerment’, and made it possible to create and access ‘different’ kinds of histories and archives (ease of global travel has of course also made new encounters and collaborations possible, but that’s a whole other issue in the struggle for social and environmental justice!). Because of technology we, LADA, can produce and distribute a DVD with Iraqi Kurdistan artist Poshya Kakil, who is rarely allowed to present her work internationally for all kinds of ‘gendered’ reasons. Because of technology we can distribute through our online shop independently produced publications by the Chinese artists He Cheng Yao and Ying Mei Duan, two extraordinary women artists usually excluded from most narratives about the Chinese art explosion. Because of technology Australian artist Barbara Campbell could not only perform her epic web based work 1001 Nights live from anywhere in the world to anywhere in the world, but could collaborate with artists anywhere in the world. Because of technology artists, archivists, scholars and curators have been able to research and create online archives and histories such as re.act.feminism and Unfinished Histories. Because of technology a new generation of writers, specifically women writers, have found a way to bypass the gatekeepers of culture and create new online and independent platforms for critical discourses around performance, and in the process led the way in framing new ways of thinking and writing with and from performance. I could go on, but you get the gist.

- The fourth wave of feminism (or whatever wave we’re in now) is an exciting time for performance as we saw in fascinating, if challenging, ways at both RRR3 Long Tables, in applications to the Fem Fresh platform, events like CPT’s Calm Down Dear and Southbank Centre’s WOW Festivals. Foregrounding and driving much of this new energy is, for me, the fierce but awesomely irreverent work of artists (re)engaging with the evolving complexities and unfinished business around issues of gender identity, of cultural difference, of the permissible, and of the possible in performance. Artists who’ve been making a mark in recent years include Katherine Araniello, Noemi Lakmaeir, Project O, Rosana Cade, The Famous Lauren Barri Holstein, Lucy Hutson, GETINTHEBACKOFTHEVAN, and Tania El Khoury. But between ‘now’ and when we set up LADA in 1999 I want to name check a few of the other artists who’ve been a huge influence, on me and on feminist art practices, specifically Kira O’Reilly, Barby Asante, Hayley Newman, Oreet Ashery, Aine Phillips, Marcia Farquhar, Yara El-Sherbini, and Rajni Shah.

- The (re)emergence of artist led initiatives and activist practices is a great thing and cause for optimism. The Guerilla Girls (and in the UK the shortlived Fanny Adams) are no longer the only feminist art activists we hear about. Pussy Riot’s altar invasion in Moscow’s Cathedral was the 21st century answer to the WLF’s 1970 stage invasion at Miss World, until Putin’s response turned it into something else entirely. Nearer home we’ve seen brilliant activist and curatorial projects by Irish artists like IMELDA and Labour that have been defined by feminist agendas and practices.

Keidan: Returning the question and bringing our conversation to a close, can you talk about some of the current artists and thinkers who are attracting your attention?

Weaver: I completely agree and am encouraged by your analysis of these three present areas of focus. I am afraid anything I might add would be repetitive. Also adding more names to this impressively long list of current practitioners would inevitably leave someone out and that would compromise our commitment to inclusivity.

However a few people and approaches do come to mind. I am aware of artists using feminism and feminist principles as methodologies for addressing issues other than feminism itself. Two examples that come to mind are Julia Bardsley in her interrogations of family and Sh!t Theatre’s exploration of the uneasy relation between unemployment and medical research. I am always on the look out for artists who have a feminist approach to their explorations of radical queer, femme and trans identities. You have already mentioned some of these artists but I would like to add, Amy Lame, Bird la Bird and Laura Bridgeman to that list. There also seems to be a lot more artists organizing themselves into collectives. They are often interdisciplinary and focus more on aesthetics than politics, but I notice that these are often influenced by feminist approaches to non-hierarchical, horizontal organizing. For example emerging companies such as Figs In Wigs are making purely aesthetic choices in their work but they organize themselves around feminist collective principles.

My work in higher education keeps me in touch with some rigorous yet accessible feminist thinkers such as Jen Harvie, Elaine Aston, Geraldine Harris and Kim Solga. I am also inspired by a cohort of emerging feminist scholars like our research assistant on this project, Ellie Roberts. Although there is a strong focus on theatre and film, I often read Jill Dolan’s blog, The Feminist Spectator for a perspective on how feminism is fairing in more mainstream culture. I am particularly inspired by the number of young women, whether university applicants, students and graduates or activists in the working world who are loudly and proudly identifying themselves as feminists. I keep updated on some global interventions by checking in on several websites including, Young Feminist Wire. It is more politically focused but lists (and funds) global art initiatives.

Shifting from our UK/European gaze, I often look to the Crunk Feminist Collective blog for enlightening and unapologetic posts on feminism, race and sexuality from a Hip Hop and pop culture perspective. Also there two Chicana artists who are pushing some important feminist boundaries both in form and content. La Chica Boom, is based in the US and creates an uncomfortable mixture of burlesque and Mexican iconography in order to explore queer racial identities. Rocio Boliver explores the materiality of her own flesh in order to critique aspects of women’s oppression and at this moment is producing some wonderfully startling imagery on the issues of aging in her project Between Menopause and Old Age.

Which brings me to my last point and a current preoccupation that has helped inform this project: intergenerationality and the ways in which we can claim and celebrate our lineages and legacies as feminist artists. To talk about this I will turn briefly to one of our most recent collaborations, Fem Fresh, that grew out of Fresh, the annual platform for emerging artists. Fem Fresh was an important part of our Restock, Rethink, Reflect initiative and was produced in collaboration with LADA as part of the 2014 Peopling the Palaces Festival at Queen Mary, University of London. It provided a platform for artists whose work focused on or around feminism and age in Live Art. We focused on an intergenerational line up both in our selection process and in pairing the artists with their mentors. The artists selected for Fem Fresh were Liz Aggiss, Chloé Alfred, The Feminist Women’s Institute, New Noveta, Hannah Stephens, Priya Saujani and Kate Spence, Emily Underwood and Jess Williams. Mentors for these artists were Ann Bean, Marcia Farquhar and Oreet Ashery. The platform was complimented by Art Tips for Girls, a series of presentations by Oreet Ashery, Anne Bean, Bobby Baker, Tania El Khoury, and Marcia Farquhar on the subjects of Live Art, age and feminism that were interspersed throughout the performances during this one-day event.

This might be a good segue into talking about how we approached this Study Room guide in general. When you suggested we work together on this project, we both admitted that, in spite of our commitment to both feminism and Live Art and our own experiences like those represented in this conversation, we did not feel like authorities on the subjects and would like to set up a method of consultation with the larger art and feminism community. We also talked about the significance of the use of dialogue in our feminist histories. With those as guiding principles, we set about developing a set of methodologies that would reflect the way feminism and feminist art have developed through conversation, collaboration and community expertise. We also wanted to experiment with alternative methods of approaching archival materials that could both highlight and enhance the Study Room. Aside from the Fem Fresh platform, some of the methods we experimented with included: Long Tables, a format for democratising public dialogue; Coffee Tables, a formalized version of an informal gathering around tea and coffee; Wikipedia Edit-a-thon, a group effort to increase public visibility of women and feminist artists; a Cocktail Seminar, a traditional panel in a non-traditional atmosphere (with cocktails!); I Wasn’t There, themed screenings from Study Room resources, and Mapping Feminism, an invitation to hand draw our journeys through feminism.

There is a separate section in the Study Room Guide that describes each of these methods and provides some tips for a DIY approach to similar conversations and archival developments.

Keidan: Thank you for this conversation, which I’ve enjoyed enormously, and thank you for everything you’ve done to conceive, research and create this Guide.